Earlier this year, diggers at West Baden Springs Hotel uncovered the long forgotten Neptune Spring on the resort’s property. Originally known as Spring #5, Neptune lies just southeast of the grand hotel on a floodplain along the French Lick Creek. The rediscovered mineral spring was one of four originally located at West Baden.

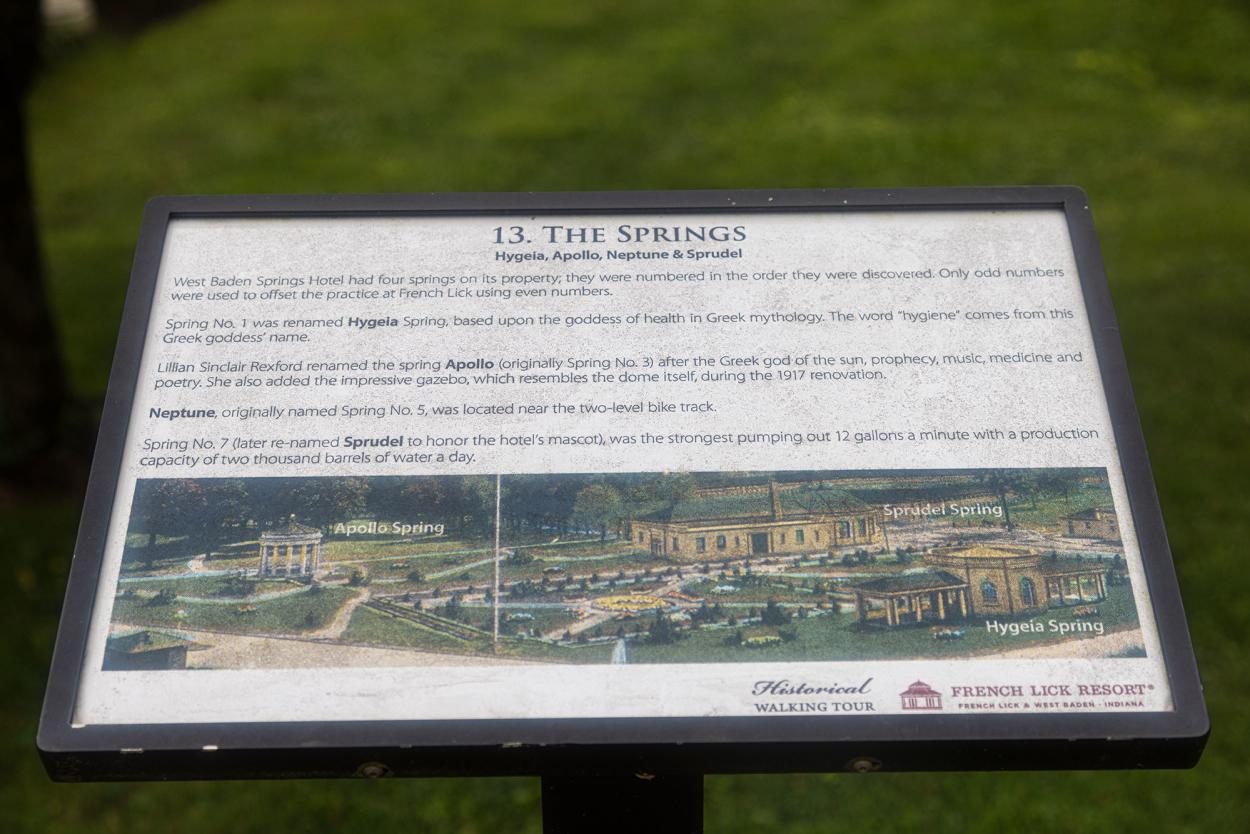

The others included Hygeia (spring #1), Apollo (spring #3), and Sprudel (spring #7). In a marketing strategy that probably only made sense in the Gilded Age, West Baden boosters labeled the springs with odd numbers to suggest that they had more than just four! The tactic was also meant to distinguish West Baden’s springs with those of nearby French Lick, who used even numbers.

After hearing about Neptune’s (re)discovery this past summer, I immediately booked a trip to see the spring. I’m of the mind that any reason is a good one to visit West Baden. Plus, as a history buff, exploring a long-lost mineral spring seemed like a valid motive to stay at Indiana’s most beautiful, most historic, and most luxurious grand hotel.

Located in what we now call Springs Valley, the mineral springs have attracted people for thousands of years. Many animals came too, including herds of buffalo lured by the salt deposits. The Buffalo Trace, a well-worn southern Indiana thoroughfare used by herds of buffalo and later by people, ran from the Falls of Ohio all the way to Vincennes, passing right through Springs Valley. Many animals would stop for water in the valley and to lick salt off the rocks. Their congregating numbers in turn attracted hunters; Native Americans initially followed by French, British, and American settlers. Years later, the state of Indiana attempted to establish a salt works along French Lick Creek around 1832, but the effort failed.

Hoosiers, however, aren’t so easily discouraged.

The first hotel in Springs Valley was built by Dr. William Bowles in the 1830s. When Bowles left to fight in the Mexican-American in 1845, he placed his French Lick House under the care of John Lane, a sometimes physician and itinerant medicine salesman. Lane began promoting the sulfur springs as a source of healing water. When Bowles returned from the war, he resumed his position as head of French Lick’s operations. An infuriated Lane established his own resort just up the road that, in time, became West Baden Springs Hotel.

The first hotel in Springs Valley was built by Dr. William Bowles in the 1830s. When Bowles left to fight in the Mexican-American in 1845, he placed his French Lick House under the care of John Lane, a sometimes physician and itinerant medicine salesman. Lane began promoting the sulfur springs as a source of healing water. When Bowles returned from the war, he resumed his position as head of French Lick’s operations. An infuriated Lane established his own resort just up the road that, in time, became West Baden Springs Hotel.

After the American Civil War, the resorts at West Baden and French Lick competed fiercely for patrons. By the end of the century, both hotels heavily promoted the restorative nature of their respective mineral springs, highlighting their supposed potent healing properties.

Pluto Water put French Lick on the map around 1900 and was known widely as a laxative. The curative water was sourced from French Lick’s Pluto Spring, though they had two others: the Bowles (later Lithia) and Proserpine springs.

West Baden on their productive Sprudel spring with the West Baden Water Company. Sprudel produced up to 2,000 barrels of fizzy water a day, at 12-gallons a minute! Sprudel’s waters supposedly contained curative properties and was peddled as a remedy for dozens of diseases, including dysentery, gout, hives, sterility, and malaria. I’m not a doctor, but I’m going to assume that valley mineral water, though deliciously bubbly, fell far short of curing anything but constipation.

West Baden on their productive Sprudel spring with the West Baden Water Company. Sprudel produced up to 2,000 barrels of fizzy water a day, at 12-gallons a minute! Sprudel’s waters supposedly contained curative properties and was peddled as a remedy for dozens of diseases, including dysentery, gout, hives, sterility, and malaria. I’m not a doctor, but I’m going to assume that valley mineral water, though deliciously bubbly, fell far short of curing anything but constipation.

But that isn’t to say West Baden’s springs aren’t magical, quite the contrary. I find West Baden to be the most magical place in all of Indiana! The discovery of the long-lost Neptune Spring only adds to the mystique that is the West Baden Springs Hotel.

West Baden has uncovered many wonderful things in recent years in addition to the Neptune Spring, including the old foundation of the 1855 Mile Lick Inn and the Apollo Spring headstone in 2018.

West Baden has uncovered many wonderful things in recent years in addition to the Neptune Spring, including the old foundation of the 1855 Mile Lick Inn and the Apollo Spring headstone in 2018.